Sign up for our free daily Olympics newsletter: Very Olympic Today. You'll catch up on the top stories, smaller events, things you may have missed while you were sleeping and links to the best writing from SI’s reporters on the ground in Tokyo.

Jack McCallum had Michael Jordan right where he wanted him. That is, the basement of Jordan’s home in the Chicago suburbs for an enviable bit of access. It was 1989, the days when the membrane dividing athletes and reporters was thin; so, looking to take the readers somewhere they couldn't otherwise go, McCallum, the esteemed Sports Illustrated scribe, ventured to Jordan’s rec room, less to describe the decor than to describe the athlete himself.

Jack McCallum had Michael Jordan right where he wanted him—again. This time, 19–15 on the Ping-Pong table, two points from victory in a game to 21. But what started as a friendly game was about to turn decidedly unfriendly. At this point, Jordan entered a zone familiar to anyone who watched him play basketball—beast mode, we might call it today. As Jordan’s eyes went from ice to fire, he informed McCallum, flatly, “You will not win another point.” Then, Jordan fulfilled that pronouncement, winning 21–19. “It was Ping-Pong and it was fun,” says McCallum. “And, at the same time, it was kind of scary.”

McCallum wrote about this game (“Ping-Pong,” the leisure activity, rather than “table tennis,” the competitive sport currently being contested in Tokyo) and how batting around a plastic ball on a nine-foot-by-five-foot green, wooden rectangle offered an insight into Jordan’s raging competitive fire.

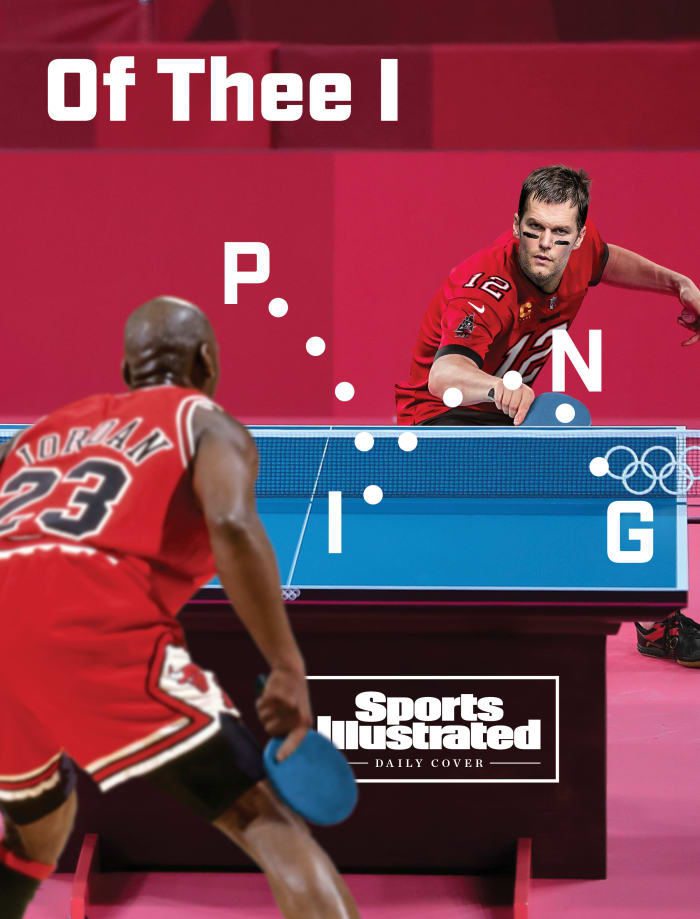

Photo Illustration by Bryce Wood; Bill Ingram/The Palm Beach Post/USA Today Network (Brady); Xinhua/Wang Dongzhon/SIPA USA/USA Today Network; Michael Kappeler/DPA/SIPA USA/USA Today Network; Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE/Getty Images (Jordan)

Little did McCallum know he was starting what has almost become its own sports subgenre: using Ping-Pong as a trope to illustrate an elite athlete’s competitive wiring. It is almost, well, a sort of parlor game in itself: Take a prominent athlete, any name-brand athlete. Add Ping-Pong. Watch it yield an anecdote about their unshakable resolve. Play along!

Jordan’s successor, Kobe Bryant, who, of course, discharged his duties on a comparable plane of intensity? Business Insider recounts a story about how “playing—and quickly mastering—Ping-Pong illustrates his insane competitiveness.” In 2013, the Lakers played in Detroit over Thanksgiving, and Bryant hosted a makeshift dinner in a room that featured a Ping-Pong apparatus. Bryant was more interested in the Ping-Pong table than in the dinner table. Mike Trudell, a Lakers beat reporter for Time Warner Cable SportsNet, recalled: “I've never competed against anybody in anything—and I played a DI sport—that felt as intense as that Ping-Pong game.”

It was a few years earlier, according to a headline, that “Cristiano Ronaldo lost a game of Ping-Pong to a former Manchester United teammate—and his reaction shows his extraordinary competitiveness.” This recalled the time Tom Brady challenged teammate Danny Amendola to a Ping-Pong game at the Patriots’ facility in 2013. As SI’s Albert Breer reported, “Amendola hammered home the last point, and barely could turn around before he heard this whistling go by his ear. Brady’s paddle had come in hot and just missed him. Amendola … looked up expecting to see Brady laughing. Instead, he was getting the death stare.”

Naturally there is a corresponding story about Brady’s rivals, too: Per a 2019 article headlined “Drew Brees turns 40: Untold stories of an ultra-competitive QB,” Brees lost a game to a teammate, left the table seething, only to return a week later as a conspicuously stronger player. “Without question, this is not an opinion, Drew Brees was practicing, either in the locker room by himself—we had a little ball shooter—or he was finding games outside of the facility,” claimed Saints offensive lineman Zach Strief. “And he can claim he didn't. But to me, that's very much Drew. One, it's important to him to win, to a point that's, like, unusual for most people.”

Let’s, well, Ping-Pong from football over to the sport of golf, shall we? Tiger Woods, we’ve been told, “doesn't take it easy on anyone, including his ex-girlfriend Lindsey Vonn. She said he won every time they played Ping-Pong or tennis.” Not to be confused with Phil Mickelson. “One of the most competitive human beings I’ve been around, whether it’s Ping-Pong, doesn’t matter,” said golfer Daniel Berger. “Whatever it is, he just wants to win.”

Steph Curry? “You can see how much it means to a guy to win,” Steve Kerr told NBC Sports last year. “And we try to do a lot of competing in practice, and you can see with Steph, any kind of competition he has to win. … Ping-Pong, same thing. The guy just has to win.” Which is virtually identical to how Utah Jazz coach Quin Snyder described his team’s star, Rudy Gobert: “I haven’t been around a player that wants to win as bad as Rudy does, even in Ping-Pong.”

Snyder’s quote was from NBA.com. Not to be confused with MLB.com, baseball’s in-house website, from which we learned, in 2015: “Clayton Kershaw is a pretty good pitcher. And when he has great games, he tends to let his emotions take over. But do you know what he might be better at and more emotional about? Ping-Pong.” You might say that Kershaw is channeling his inner Lewis Hamilton, the British Formula One driver, who once declared: “I hate losing. It doesn't matter if it's racing or playing Ping-Pong—I hate it. You’re either first or your last.”

It was Mao Zedong who once wrote a manual on table tennis, referring to the sport as “a spiritual nuclear weapon.” Maybe he was onto something. What is it about Ping-Pong—this rec room and barroom staple that tends to resist serious treatment—that also makes it into this accelerant for competitive flame?

We put this to Michael Lardon. From his base in San Diego, Lardon is a prominent sports psychologist, who works with top Olympians, PGA golfers, and even UFC fighters. Before that, though, he was a professional table tennis player, touring the world to compete, blasting his forehand drive at more than 100 miles an hour.

Some of the reasons Ping-Pong finds favor among elite athletes are obvious: Everyone plays. (Almost literally—weighted by its ubiquity in China, table tennis is generally regarded as the world’s most popular sport.) Everyone knows the rules. There is little risk or fear of injury.

But beyond that, the same qualities that make Ping-Pong so casually social make it fiercely competitive. For one, there is the absence of distance between the competitors. “Elite athletes love competition,” says Lardon, “and intimacy heightens the feeling of competition.” When your opponent is nine feet away, looking you in the eye, and you hear every morsel of trash talk, it arouses intensity.

That Ping-Pong demands touch and precision and strategy, but not brute strength, creates, to mix sports metaphors, a level playing field. At 7' 1", Rudy Gobert, for instance, isn’t going to take much satisfaction at beating people one-on-one in basketball. But at the Ping-Pong table, he’s part of a fair fight, one that certifies hand-eye coordination and superior tactics and mental strength.

Decades later, recalling his game with Jordan, McCallum notes that beyond hitting the ball past an opponent or lacing it with devilish spin, Jordan enjoyed “the mind f--- games.” Lardon agrees, while offering a slightly more clinical take. “Again, because of the physical intimacy, players often try to psych their opponents out and get into their heads, which appeals to competitive individuals.”

And, playing Ping-Pong, they get into their own heads as well. Says Lardon: “Great athletes often find the mental zone in their sport. Table tennis, because of its speed and neurological demands, takes full attentional focus. If you blink an eye, the ball is gone. It is a sport that, by nature, sets conditions that facilitate zone-like experiences, which is what elite athletes seek.”

Because of these qualities, Ping-Pong is sometimes used as a therapeutic exercise for people with ADHD and various cognitive impairments. And, more and more—and often under the guise of recreation or team bonding—Ping-Pong is used by smart coaches and sports executives. For the last several Ryder Cups, organizers have flown in a Ping-Pong table for the American team to use. When the Falcons reached Super Bowl LI, management attributed it in part to the team’s Ping-Pong competitions. Most MLB spring training facilities now include a team Ping-Pong table as well.

As for the most competitive of them all, Ping-Pong would stoke Jordan’s competitive fire long after the dust-ups in his basement. And McCallum, who had experienced this firsthand, was there to chronicle it. In his excellent book Dream Team, McCallum recalled, “Any number of people can relate horror stories of playing Ping-Pong against Jordan, who was very good but not great, beatable on paper but generally not in reality since he wore almost everyone down with relentless aggression and psych game.”

At one point during the Dream Team’s stay during the 1992 Barcelona Games, Jordan played NBA executive Steve Mills and declared “I will NOT let you go home and tell your friends you beat me.” He did not and he did not. Jordan allegedly lost to teammate Christian Laettner, went into a fury, practiced surreptitiously and won a rematch, 21–4. (For the record, asked about this game, Laettner professed to have no recollection.) Jordan also played furious games against NBA commissioner David Stern. And that’s just the Barcelona Olympics.

In his biography of Jordan, aptly titled Playing for Keeps, David Halberstam wrote, “If you beat Jordan at Ping-Pong … then you had to play again—and again—until finally he won.” In multiple books, Phil Jackson references Jordan’s fury when playing Ping-Pong. It also figured prominently in an academic paper by a Polish sociologist, Tomasz Jacheć, titled, “Competitive Spirit as a Form of Behavioral Addiction: the Case Study of Michael Jordan.”

Yet Lardon would argue that Jordan’s competitive zeal with a paddle in his hand is not addiction. It’s a healthy outlet, a space where—far from cheering crowds and cameras and commercial pressures—elite athletes can maneuver a little plastic ball through air and prove that they are really good at their day jobs.

• Inside Alex Cora's Second Chance

• How Noah Lyles Recaptured His Former Life

• In the Pool, Caeleb Dressel Is the Ultimate Spectacle