Chest heaving in the water, Ryan Lochte peers at the whiteboard above him and despairs. It is mid-February, and the 36-year-old has already devoted four hours to pulling himself through the pool, another exhausting day in an unrelenting string of them. Now, instructions scrawled in black dry-erase marker demand he wring nine more 300-meter sets, with little rest between each, from his already burned-out body.

When the second-most-decorated men’s swimmer in Olympic history finishes those merciless final 2,700 meters, he flings his swim cap and goggles against a wall behind the starting blocks. On his way to the locker room, limping noticeably, he shuffles under a University of Florida records board that bears his name five times, though his marks read like relics (even if his 200-meter individual medley world record still stands). The most recent was set in 2012, an eon ago in a sport that favors youth. Reminded of that reality by the sting in his muscles and joints and lungs, the 12-time Olympic medalist plops down on a bench and begins to sob. The pain is the price of his improbable pursuit: a return to the Games this summer in Tokyo.

Still despondent, Lochte makes the 20-minute trip to his new home in an unremarkable subdivision in west Gainesville, Fla. His father, Steve, rides shotgun in Lochte’s slate-gray Chevy Tahoe, having learned long ago to let Ryan’s breakdowns—whatever their cause—pass unacknowledged, wary of amplifying the hurt. This marks the third time in recent months that Lochte’s legendary tolerance for physical pain has reached its limit. “Week after week, practice after practice, the intensity that he puts in, he gets to a point of mentally breaking,” Steve will say later. “It’s his body crashing. His mind has been strong enough to hold it together—and then, eventually, it snaps.”

Lochte is greeted on this night by hugs from his children: three-year-old Caiden and one-year-old Liv. For the entirety of his adult life, Lochte says, he guzzled booze in extravagant volumes to dull the aches bred by his sport and the spotlight. But after spending six weeks in outpatient treatment for alcohol use in 2018, he says that big smiles and little squeezes from a young son and a baby girl are sufficient salves. After embracing the kids, he swills a beer on the couch, which he says helps wash those last 2,700 meters away, but he doesn’t crack open another.

Because his tolerance for pain has long been matched by his tolerance for alcohol, the people who love him most have had to learn to tolerate him, each mistake costing trust and money and an Olympian’s most valuable commodity, time. To atone, he has convinced himself that the final miles of water ahead of him are more important than the thousands in his wake.

He is fixated on redemption: both the shallow sort that brands and broadcasters could sell this summer, enriching him and his family, and a more substantive kind. He is certain that if he rebounds and becomes the U.S.’s oldest-ever men's Olympic swimmer—or even perhaps the oldest individual gold medalist—in Olympic swimming history, he will finally salvage his legacy, among both loved ones and the masses.

Really, though? At 36?

Both Lochte’s father and his coach insist this isn’t some quixotic quest. Steve declines to share specifics, but talks of practice times on par with those logged a decade ago, when Lochte was breaking world records and piling up medals. Like the rest of the family, Steve desperately wants his son to find peace.

“Everyone around me is putting a lot of pressure on me—more than I’ve ever had in my entire life,” Lochte says. “I feel it from everyone. Like my family. The people that live in this house. My agent. It’s just everyone.

“I feel like, if I don’t [make it], I’ll become a failure.”

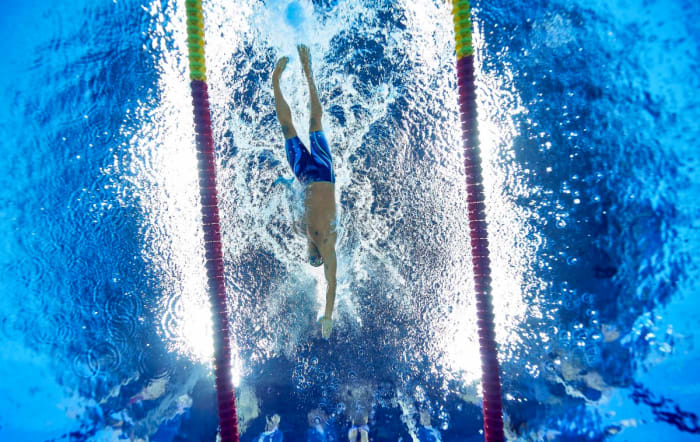

Lochte raced as part of the U.S. men’s 4x200 freestyle relay team in the 2016 Games (above), helping to snag gold with his 1:46.03 leg in the final.

Donald Miralle/Sports Illustrated

When Steve dropped off Lochte at Florida in 2002, then assistant coach Anthony Nesty could sense apprehension in the teenager’s father, who had long doubled as Ryan’s swim coach. As he led Lochte away, Nesty turned to Steve and assured him: “Coach, we’ll take care of him.”

Three weeks later, the Gators’ head coach (and Steve’s close friend), Gregg Troy, called to report that Lochte had stumbled out of a Florida football game and sliced his hand open on a shard of beer bottle. Lochte had been drunk before—he says the first time came in high school, after he and friends tossed back some Mike’s Hard Lemonade—but now he lived in a town laden with dollar beers and cheap shots, and where his propensity to run through life at full bore could easily translate to dangerous excesses. From then on, Lochte would be watched over by a cadre of caretakers.

Over time, Lochte’s teammate and roommate Elliot Meena learned that he could help the Gators most not by stacking up points at meets, but by keeping Lochte upright enough so that he could do that. “I had to keep his head out of the toilet and [him] from choking on his own puke,” Meena says. “If I kept Ryan healthy and eligible, single and sober—just awake—those points I felt somewhat [responsible] for.”

When Lochte arrived at the pool reeking of alcohol, coaches tended to go easy on him, because he’d still dominate every single practice rep. Steve and Troy shared a mantra: If you’re going to be a man at night, you have to be a man in the morning. So Lochte lived by it, outdrinking anyone who tried to keep pace under the neon lights, and then outracing them at sunrise, along the way accumulating seven NCAA championships. No matter how he treated it, Lochte’s body was always able to do what he demanded of it in the pool—and more. “I’ve worked with a lot of Olympians, a lot of gold medalists, and I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody who can endure the way he does,” says Matt DeLancey, his strength coach at Florida.

After returning from the 2004 Olympics with a pair of medals, Lochte morphed into a campus celebrity, holding court at the Grog House, a dingy bar in Gainesville where he bought drinks for strangers and often slipped behind the bar to hand out shots. From the time he was a child, Lochte’s motivation had been to please those around him. In his youth, that meant refining his backstroke for Steve; in college, it meant being the sun around which the Gainesville party scene revolved. (The house he rented with Meena and other swimmers had $5,500 worth of damage to show for it when they moved out.) Lochte also had a propensity to rip signs and posters off walls when he had been drinking; he faced no consequences for this destructive habit in Gainesville.

Another Olympic cycle later, having collected four more medals at the 2008 Beijing Games, Lochte, then 24, used his newfound international fame and substantial endorsement deals to fuel a supercharged version of his old college life. His brother Devon, six years younger, moved into the off-campus house Lochte had purchased after graduating in ’07. And while Devon idolized Ryan, he grew alarmed as the crowd of hangers-on grew wider and their connections shallower. Four nights a week, bouncers would usher Lochte past lines, and he would become the evening’s entertainment wherever he flashed his Ralph Lauren–sponsored smile. To Devon, it seemed the entire town was eager to drink on his brother’s perpetually open tab.

Friends say Lochte handed out expensive watches and wallets like party favors. He surprised people by paying for lavish sound systems to be installed in their cars. He bought four Xboxes at a time, intent on giving them away. He once returned home with $30,000 in winnings from an overseas event and gave away $1,000 to a loose acquaintance who dropped by to ask for that much in “gas money.”

“For other people to come in and take advantage of his hard work, I wasn’t a fan of it,” Devon says.

Despite his high-octane lifestyle, Lochte, for a time, rivaled Michael Phelps as the best swimmer in the world. At the 2011 World Championships, in Shanghai, he won five golds and a bronze, and he edged Phelps in the 200 freestyle and 200 individual medley, setting a world record in the latter that still stands. The ’12 London Games would bring five more medals.

In 2013, E! aired an eight-episode reality series, ironically titled What Would Ryan Lochte Do?, in which the by-then-famously loutish celeb-athlete pounded tequila shots the night before an early-morning practice, contemplated publicly urinating on at least one national monument and attempted to make various catchphrases happen. Meena, watching at home on TV, says he had trouble telling whether his old roommate was being his genuine self—an occasional dunce, but unrelentingly kind—or playing the part of a vapid and obnoxious party boy to please the masses. The wall between the two had started to erode.

Cullen Jones, a teammate of Lochte’s on the U.S. Olympic team, understands how TV viewers saw his close friend: “He was depicted as a dumbass.” But he also believes the show missed a lot. “He is a professor when it comes to swimming,” Jones says, insisting he’s never met anyone, aside from Phelps, who better understands the intricacies of the sport.

Jones felt that most of his friend’s positive qualities—like his generosity—were absent from the show, steamrollered by the self-obsessed image Lochte was projecting. At major events, for instance, Lochte often hung around late signing autographs—longer than anyone else on the team, Devon says—even when it cut into his sleep before a race. (Lochte says he remembers as a child approaching an Olympic swimmer in an elevator, being denied an autograph and vowing never to make a young fan feel the way he had.)

Troy saw, too, what TV cameras didn’t: how Ryan had grown estranged from his father after Steve and Ileana Lochte divorced in 2011; how that gnawed at him; and how he grew more erratic. Lochte’s commitment in the pool began to wane, Troy says.

“I was like a rock star in a small town,” Lochte says of that time. “It just kept going and going. Then I started getting in trouble.”

In October 2013, Lochte packed up and moved to Charlotte, to train with Jones, leaving Troy and his old life behind—though not his old vices.

Phelps (center) and Lochte have clashing personalities, but have grown closer as Lochte chases redemption.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

In the early morning of Aug. 14, 2016, Kayla Rae Reid’s phone rang in her Rio hotel room. Lochte’s girlfriend of seven months, Reid, a model, was sharing a room with his mother, Ileana, so she slunk into the bathroom to answer. Lochte had been out all night celebrating the end of his fourth and perhaps final Olympics, which had culminated in a gold medal in the 4x200 freestyle relay, but now his voice was trembling. “All I heard,” Kayla says, “was gun and wallet.”

Later that morning, on a shuttle bus, Ileana spilled the incendiary story to an Australian reporter: Her son, a decorated Olympic medalist, had been robbed at gunpoint. From there, the tale spread like wildfire through the media in Rio, until NBC’s Billy Bush spotted Lochte by the beach and on a cellphone recorded the interview that would reshape Lochte’s life. Still buzzed from the night before, Lochte told Bush that he and three teammates had been pulled over in their taxi, and that someone in a group posing as policemen had pointed a gun at his forehead and stole his wallet.

Within days, Brazilian police had pulled the story apart. Surveillance footage showed the teammates’ getting out of their cab and urinating in bushes behind a gas station and Lochte’s ripping a loose-hanging sign off a wall, as he had been prone to do in college. A security guard did intervene, pointing a gun at Lochte (albeit not squarely at his forehead), and the swimmers did hand over some cash—but the money was extracted, purportedly, to cover the damaged sign. Suddenly, the story became that an ugly American—a diamond-grill-wearing, bleached-blond symbol of entitlement—had played on negative stereotypes about Brazil to cover his own misdeeds.

While Lochte hastily and repeatedly apologized, the many caretakers around him wondered whether they had dropped the ball by not chaperoning him that night, by not holding those tenuous guardrails in place. Lifelong friend and college teammate Kyle Deery was in Rio but didn’t go out because he had a flight home the next day. Devon partied with his brother for several hours but left early. Jones didn’t qualify for the team that year. Had he been there, he laments that he may have been able to steer his friend away from self-inflicted peril. Five years later, Kayla wonders whether things might have turned out differently if she’d chosen revelry over rest. “Would we not have stopped to go to the bathroom?” she asks. “Would they have even gotten that drunk?”

Lochte finally slipped when no one was there to catch him, and the resultant injuries were severe. Seven figures’ worth of sponsorships evaporated, from the likes of Speedo and Ralph Lauren. A 10-month suspension was levied, and death threats were lobbed. Young fans told him he’d failed them. Kayla soon struggled to land modeling jobs and, for the sake of her career, those close to her suggested she leave him.

Rio should have been a high point; instead, Lochte slipped into a depression, shutting out Meena and other friends. Devon says he listened to his brother weep over the phone. “I figured he was just holed up drinking and trying to forget,” says Deery.

Suddenly, retirement was off the table. Lochte says he assured himself the only way to reclaim his name was to spend four more years in the pool, whatever his age. He also decided to return to Gainesville—to Troy and DeLancey. To the structure that had gone missing in his life.

Finally, in October 2017, a year after they were engaged, Ryan (whose credit was so poor he couldn’t qualify for a home loan) and Kayla left their a $5,500-a-month Los Angeles townhome, eventually settling in a modest 1,800-square-foot apartment near his old Florida campus. Kayla admits now: The thought of her fiancé returning to his old haunts and habits was troubling, but she hoped the reunion with Troy would keep him in line. “I was terrified,” she says. “I keep Ryan in Bubble Wrap. I just have to watch every little thing.”

Ironically, it was Kayla who fell ill in May 2018 (four months after she married Ryan), which led the couple to visit a clinic for B-12 infusions, which blew up in their faces when Lochte posted an Instagram photo, husband and wife seated below two half-full IV bags. After the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency hit Lochte with a 14-month ban—B-12 injections are not specifically off-limits, but any intravenous injection over 100 milliliters is against the rules—he felt like he was approaching bottom.

On Oct. 4, 2018, following a sponsor event in Newport Beach, Calif., and a night of drinking, Lochte found himself locked out of his hotel room and tried to kick down the door. Security swarmed him, moved him to a new room and asked him to leave first thing in the morning. The next night, shortly after landing back in Gainesville, he rear-ended a car on the way home from the airport. Police did not cite alcohol as a factor in the crash, but the two incidents made easy TMZ headlines, and Kayla was shattered. “How much more can I take?” she remembers thinking. “Get your s--- together, or else who knows what can happen.”

At least one person had enough. It was around this time that Lochte’s relationship ended with DeLancey, who recalls: “At that point, I wanted him to get help more than I wanted him to be a great swimmer.”

Lochte has returned to Gainesville to train for his one last shot at Olympic glory.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

There are different accounts of how Lochte found his way to treatment. Jeff Ostrow, Lochte’s attorney-agent, says he urged his client in that fall of 2018 to enroll in an outpatient alcohol use treatment program at the University of Florida. Lochte, though, insists the impetus to seek help came from within. He also rebuffs, for the record, the notion that he was ever dependent on alcohol. “I was never addicted,” he says, at the same time admitting that “anything I’ve ever done [wrong] . . . was with alcohol, so I knew I had to take a step back and change something.”

For six weeks Lochte heard horror stories about how drinking had upended the lives of those in treatment alongside him. He would put in full days in the program, then come home and confide in Kayla what he says he’d learned about himself—about his compulsion to make others feel good, to live up to the two-dimensional caricature of himself that he’d embellished in front of cameras and packed bars.

In the meantime, Ryan and Devon reconciled with their father, who remarried and started making regular visits, keeping an eye on Lochte’s technique as he trained with Troy. (Lochte is now estranged from his mother and hasn’t spoken to her in several years.) Ryan still drinks the occasional beer, but Steve has been pleased to see him eschew events like wedding after-parties to get to bed early. “You don’t need to get drunk,” Steve says. “Those days are over.”

Lochte’s circle has shrunk, but he has reengaged and made good with close friends, holding monthly Zoom chats with an inner circle. Earlier this year, DeLancey was sitting in his living room, watching the evening news, when a familiar name flashed across his phone. About two years had passed since he’d last spoken to Lochte; now the strength coach counts that conversation among the most meaningful of his life. “For him to apologize,” he says, “that’s a big step.”

That call was private. A more public mea culpa was planned to have occurred on a CNBC show, Back in the Game, hosted by Alex Rodriguez, when producers cajoled Lochte to reach out to Phelps for an on-camera apology. Lochte remembers how the request irked him, but he dialed anyway, ever the pleaser. Phelps—who has publicly addressed his own struggles with alcohol and depression, and who has called attention to the mental health strain on athletes after the Olympic machine spits them out—didn’t answer Lochte’s first call, on camera, but the old teammates connected later, and it prompted an ongoing dialogue.

Though long portrayed as polar opposites, both men found they dealt with comparable pressures, and Phelps still checks in on his old rival as Lochte chases something that not even history’s greatest swimmer ever accomplished. “After that apology, he was like, ‘I’m here to help you,’ ” Lochte says. “I love him for it because he’s been through it.”

While teammates catnap between training sessions, Lochte goes home to Kayla and kids Liv (left) and Caiden.

Simon Bruty/Sports Illustrated

Lochte’s suspension lifted just as Troy was returning from the 2019 World Championships in South Korea, and the coach was flabbergasted when he laid eyes on his eldest pupil. Without Troy’s constant oversight, Lochte’s weight had swelled to 217 pounds, about 20 pounds heavier than when Troy had left, a month earlier.

Still, at Lochte’s first meet after the suspension, the U.S. National Championships, he won the 200 IM, finishing in 1:57.76, good enough to qualify for a spot at the U.S. Olympic trials. (Troy keeps a photo of Lochte spilling out of his swimsuit at that event, to remind him of the consequences of losing focus.) Lochte had slimmed down and was rounding into form last March when COVID-19 postponed the 2020 Games.

“Training for another Olympics is one thing,” says Jones, “but having to do it for another year, that is his penance for what happened [in Rio].”

Lochte has indeed served penance in a variety of ways: Last August, he underwent an emergency appendectomy and, simultaneously, hernia surgery. The stamina of an elite (and peak-aged) swimmer can diminish in mere days out of the pool; here Lochte was forced to spend two weeks dry . . . and the next four limited to light activity in the water. Three years into a rigorous Olympic training cycle, he had to start from square one, and Steve confided in Troy that he sensed his son had begun to doubt whether he had the resolve—or the ability—to press on. In November, Troy pulled Lochte aside and told him bluntly: “You don’t have to do this.”

Lochte, steadfast in his belief that standing on an Olympic podium one last time was his only means of providing for his family and rebuilding his legacy, insisted that he did. And so the coach told his 36-year-old pupil—recovering from surgery, battling through a pandemic-induced delay—to prepare for the most grueling year of his life. And Lochte has since leaned into the pain. “That’s a strength,” Troy says. “He’s not afraid to go where a lot of people don’t want to.”

Lochte trains today as part of the 11-member Gator Swim Club, a group laden with Olympic hopefuls. His salt-and-pepper hair concealed by a swim cap, he is a full decade older than any of his teammates. When they step to the blocks, Lochte looks like a vintage muscle car taking on a fleet of Ferraris. He can no longer win every practice rep, like he did in college, but Troy insists Lochte can still intermittently hang with 24-year-old club teammate Caeleb Dressel, perhaps the world’s top men’s swimmer, who appears on track for a Phelpsian medal haul in Tokyo. Those two swim a lane apart in practice, and Lochte often imparts advice, even though Dressel may one day soon compete with him for the crown in the 200 IM.

The U.S. allots only two qualifying spots in that event, which appears to be Lochte’s best chance to make the Olympic team. Among the Americans in the running for those two slots at the June trials, in Omaha, Lochte’s qualifying time (1:57.76) stands fifth, though that came when he was overweight. He has not yet raced in peak condition.

Every week, Lochte swims between 50,000 and 60,000 meters, spread across nine sessions. Near the end of one mid-February practice, he told an assistant on the pool deck, “I’m f------ beat,” before lowering his head into the crook of his arm and shaking it, as if negotiating with the pain. “It just keeps adding up,” he says. “I’m carrying 1,000 pounds on my back every day.”

That isn’t limited to swimming. Now a father of two—Liv was born in June 2019—Lochte spends the time between two-a-day sessions rolling around on the floor or running in the backyard, rather than napping, like his younger teammates.

In January, Lochte and Kayla finally bought a home of their own, a freshly finished two-story craftsman on a corner lot, in a neighborhood that would look familiar to any semi-successful thirtysomething, its granite countertops and oversize ottoman littered with children’s toys. It’s not of the stratosphere they once occupied—the Porsche and Range Rover are gone—but both husband and wife say that owning a home has proved a meaningful milestone, their first quantifiable measure of stability after a relationship beset by chaos.

Having squandered millions, Lochte has gradually rebuilt a now-six-figure sponsorship portfolio. In addition to the swim-apparel brand TYR, he’s a spokesman for an Ohio sports academy, and he recently launched a fitness service, Loch’d In Training, that allows subscribers to do gym workouts with him over a livestream. During the debut session, in February, he shouted encouragement to the 16 people who’d logged on, agreeing to pay $12.99 per month (or $108 for a full year!) to train with an Olympian. That scene, inside an empty gym, seemed far from any medal podium.

While Troy is coy about Lochte’s progress in the pool, Steve remains adamant that his son’s story will end in Olympic glory. “We’re going to break the world record,” he says, unflinching. And if that doesn’t happen? Friends wonder how the disappointment of not medaling or, before that, not making the team, might affect Lochte, who remains a work in progress, not a finished product.

Win or lose, the plans for what comes next are a bit scattershot. Maybe Lochte will coach swim clinics. Maybe he’ll helm a pro team. Maybe some motivational speaking. Maybe a mix of it all. Kayla envisions their bumpy life story translated to a film, in the vein of I, Tonya. (She wants Margot Robbie to portray her; Lochte sees Matthew McConaughey playing him.)

But what happens when his Olympic saga reaches its denouement, in August? “That’s what I’m worried about,” Steve says. “We are trying to figure that out.”

Before Lochte faces those looming uncertainties, he still has months more of training ahead of him, hoping the pain that awaits might finally free him of the hurt.

More Olympics Coverage:

• Most People in Japan Oppose the Olympics. So Where is the Opposition?

• Larry Gluckman Leaves Behind Legacy Greater Than Rowing

• Health Experts Say Tokyo Olympics Must Be 'Reconsidered'